2023 Forest Management Policy Playbook: State Strategies For Forest Restoration And Wildfire Response

By Kendall Cotton, Hannah Downey - January 23, 2023

Download Report

2023 Forest Management Policy Playbook: State Strategies For Forest Restoration And Wildfire Response

By Kendall Cotton, Hannah Downey - January 23, 2023

Download Report

Summary

State leaders can expand proactive forest restoration and wildfire response capabilities by encouraging collaboration, reducing conflict, and leveraging strategic investments. Nearly 9 million acres in Montana face very high or high wildfire risks, but improving active management of forests to prevent catastrophic fires and improving response capabilities when fires do break out can reduce the harmful impacts to Montanans.

Actively Manage Forests With Prescribed Burns

Problem:

Overgrown forests are a leading cause of catastrophic wildfires. The buildup of fuels, including brush, undergrowth, and small-diameter trees, leads to wildfires burning hotter, faster, and bigger when they start. Increasing active forest management, notably the use of timber harvest and prescribed burns, to clear out excess fuels is necessary to fix our forests.

With a third of all forests in the state on non-federal lands, Montana has the opportunity to increase the use of prescribed burns on private lands as a way to proactively reduce our wildfire risk and protect private lands as wildfires spread from other sources. Time and time again, when wildfires have spread to areas where prescribed burns have been applied those fires have become less destructive and easier to fight – especially when combined with mechanical thinning.

The good news is that Montana has an efficient prescribed burn permitting system and emphasizes the use of general permits to conduct a prescribed burn on private lands, while also forecasting burn days a week in advance.

The challenge, however, is that Montana does not have a clear standard for determining whether a landowner is liable for the damages of a prescribed fire that escapes, which seriously discourages the use of prescribed burns on private lands. Certainly, burners who do not responsibly administer burns must be held accountable for damages done, but significantly less than 1 percent of prescribed fires escape to cause damages–and most of the escaped burns only cause minor damage, such as burning a small area of neighboring forest or grassland.

Montana should clarify its prescribed burn liability standard and consider adopting a gross negligence standard which has been shown to significantly increase prescribed burn use. Additionally, a catastrophe bond should be created to help cover any potential damages when prescribed burns do escape.

Solution:

Clarify prescribed burn liability standards while protecting against potential damages.

Option #1:

Improve liability regimes to align private risk and public benefits of prescribed fire.

Despite the benefits of managing land with prescribed fire, many private landowners decline to adopt the practice due to fear of liability. Ordinarily, holding people liable for the harms they create works well to encourage responsible behavior and discourage carelessness by requiring people to internalize risks and costs imposed on others. In the prescribed burn context, however, it has produced closer to the opposite result. If landowners bear all of the costs and risks of prescribed fire while capturing only a portion of the benefits, they will likely decline to use the tool even when the total benefits far exceed the risks. Montana’s liability standard for prescribed fire is currently uncertain, making it even more difficult for landowners to understand their liability risk when conducting burns.

To improve the use of prescribed burns on private lands, the legislature should clarify the liability standard and also consider a gross negligence standard, which has been shown to boost prescribed fire use by 10 percent.

50-63-105 Liability for prescribed burns

(1) When a prescribed burn is conducted on private property, the landowner or his agents is liable for property damage resulting from an escape only if it resulted from the person’s gross negligence.

Option #2:

Utilize tools like Catastrophe Bonds.

While reducing landowners’ liability for escaped prescribed fires is essential to expanding use of the tool, shifting that risk to surrounding landowners and communities may undermine support for “good fire.” An innovative, market solution to this problem would be to use a catastrophe bond to cover damages in situations where a burner was not negligent. Catastrophe bonds are a widely used tool to reduce exposure to low-probability but high-cost events.

Investors would pay into the bond, which would generate financial returns through contributions from those who benefit from the reduced risk of wildfire through prescribed burns, including the state of Montana. The Department of Natural Resources and Conservation and the state legislature can encourage prescribed fire that reduces future fire suppression costs, threats to public property and infrastructure, and impacts to environmental resources by providing financial returns to catastrophe bond investors. Utilities and insurance providers might similarly benefit by reducing their exposure to wildfire-related liability. In exchange for reduced liability, prescribed burners could pay a fee on burn permits that would also fund bond returns.

Next Steps: Direct DNRC to study the option of implementing a prescribed burn catastrophe bond in Montana.

Continue Leveraging Local Forest Management Resources

Problem:

The Federal Government owns nearly 30 percent of the land in Montana, making them the largest forestlands manager in the state. The Montana Forest Action Plan identifies 3.8 million acres as the state’s highest priority for forest restoration work, 60 percent of which are on federal land. With limited resources and bureaucratic red tape, federal forest restoration projects have been met with severe delays, further contributing to the wildfire crisis.

2021 Bootleg Fire – Source: S. Rondeau/Klamath Tribes’ Natural Resource Department

Through the Good Neighbor Authority, the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation is able to plan and implement forest restoration projects and address shared priorities on federal U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management lands in the state. Under the Good Neighbor agreement, Montana is able to use state procedures, personnel and contracts to carry out activities such as thinning or administering prescribed burns and can sell timber harvested from federal forests. Revenue generated from timber sales is retained by the state and can be reinvested in future forest projects to get more work done on the ground. Montana has reached a position where these timber sales are generating enough revenue for the Good Neighbor program to be self-sustaining.

Solution:

Empower local decisions and actions on forest management.

Option #1:

Continue to proactively seek out opportunities to expand Good Neighbor Authority projects across federal forestland and identify projects with revenue-generating potential.

Montana currently has Good Neighbor agreements in place with both the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. Since projects began in 2018, the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation has eagerly put the agreements to use. The state has used GNA to treat 26,000 acres of forest lands with tools including timber harvest and prescribed burns. At least 37 timber sales and 39 restoration projects have been completed or under contract through GNA. As a result, over 83 million board feet of timber have been harvested, generating $14.3 million in revenue–making the program financially self-sufficient.

Montana has proven capable of scaling up forest management on federal lands through Good Neighbor Authority. While federal land agencies also need to increase active management of federal forests, the state should continue to pursue Good Neighbor Authority projects that promote forest health, reduce wildfire risk, and support the Montana timber industry. The state should also support federal reforms to make counties and tribes equal partners under Good Neighbor Authority.

Option #2:

Explore the possibility of charter forests in Montana.

A major challenge to increasing active forest management is the many bureaucratic hoops forest managers must jump through in order to make decisions. One approach that could build on the lessons learned of devolving management through Good Neighbor Authority is the creation of state charter forests. Similar to a charter schools approach, charter forests would remain under state ownership but would be managed by a board of accountable stakeholders. The state would maintain oversight, including setting broad land use goals and performance standards, but charter forest managers would have the flexibility to develop and implement innovative local solutions.

Montana could be the first state to pilot a charter forest management approach. A previous Republican presidential administration and an Idaho land reform committee have endorsed the concept of charter forests. To put the idea into practice, Montana should commission a study of how charter forests could be applied to improve the management of state forests.

Upgrade The Montana Fire Force

Problem:

The effects of delayed attack on unnaturally severe wildfires can be devastating on Montana’s economy, and by extension state revenues. The costs of effective early suppression pale in comparison to long drawn out fire campaigns that persist for weeks or months.

Thankfully, Montana boasts a treasure of homegrown fire-fighting assets, including some of the nation’s largest and most capable aerial firefighting fleets. The MT DNRC currently maintains a fleet of aircraft on a Call-When-Needed (CWN) contract basis, where availability is based on the availability of the aircraft.

However, under CWN contracts there is no contractual guarantee that the asset will be available to be used on Montana fires when the state calls, as resources could be working missions in other states with earlier fire seasons.

This dynamic makes Montana’s aerial wildfire response often reliant on coordination with federal agencies and other states to dispatch aerial firefighting assets to Montana fires, which adds more bureaucracy to wildfire response and undercuts the state’s commitment to aggressive initial attack.

Solution:

The state should specifically allocate fire suppression funding towards upgrading the MT DNRC’s Montana-based fleet of firefighting assets from CWN contracts to Exclusive Use (EU) contracts for the summer months.

Montana should prioritize securing aerial fire suppression assets in state-on-state contracts and adopt a goal of becoming completely self-sufficient, freeing our state from reliance on the federal government or other states for aggressive wildfire response. This would best be accomplished by upgrading contracts for the state fire force to support aggressive initial attack within state borders.

Benefits of upgrading the state aerial fire force from CWN to EU contracts:

- Guarantee the availability of an aerial firefighting asset for a defined period of time, rather than CWN contracts which rely on the availability of an aircraft.

- Enable Montana to dispatch resources rapidly and decisively in support of state firefighting objectives on private, state or federal land without reliance on the federal government or other states.

- Reduce costly delayed attack due to bureaucracy and likely save taxpayer dollars over the long run – not to mention protecting the lives and land of Montanans.

The state can also reduce its cost burden for maintaining EU contracts by dispatching assets to support other states with active fires when they are not needed in Montana. In these scenarios, Montana’s costs for maintaining EU availability would be reimbursed through cooperative agreements with the other state and federal agencies receiving our support.

The bottom line is that Montana should control its own wildfire destiny. Putting in-state wildfire assets under the state’s exclusive control will enable our state to be self-sufficient in fighting unnaturally severe wildfires.

Create A Model Mitigation Certification Program For Homeowners

Problem:

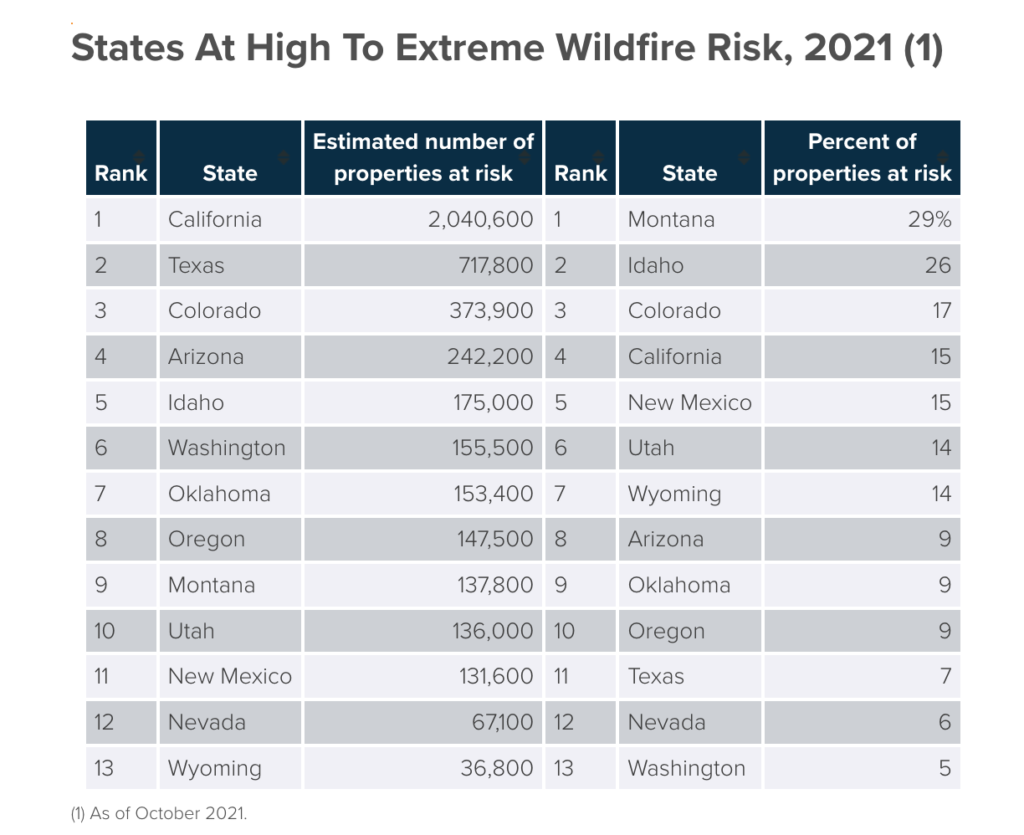

Nearly 30% of Montana properties have extreme wildfire risk, more than any other state. This extreme risk can impact the availability of home insurance for thousands of Montanans as insurers increase premiums to compensate for the risk, or decline coverage completely.

Source: https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-wildfires#Top%2010%20Costliest%20Wildland%20Fires%20In%20The%20United%20States%20(1)

While home insurance is not required by law, many mortgage companies require home insurance. Declined coverage can be devastating for those relying on financing for their home, while expensive coverage can put home insurance out of reach for less wealthy homeowners. Additionally, no insurance puts Montanans at a great risk of unrecoverable losses from property damage by wildfires.

A standing advisory memo from Montana’s Insurance Commissioner clarifies that insurance companies cannot outright deny coverage based solely on the fire risk present in the home’s geographic zone, such as a zip code. However, insurers aren’t prohibited from denying coverage based on a case-by-case assessment of fire risk.

Solution:

The state should create a model voluntary wildfire mitigation certification program, led by the Insurance Commissioner.

Fire mitigation efforts can increase the chances that a home at risk of wildfire will remain insurable. Some Montana insurers have already adopted mitigation incentive programs, which offer premium discounts in exchange for community homeowners voluntarily achieving a FireWise USA recognition for reduced wildfire risk.

Montana leaders can champion the development of these voluntary mitigation programs to help Montana homes remain insurable in the face of wildfire risk. Leaders in Boulder County, CO have collaborated with insurers to create Wildfire Partners, an innovative program which helps homeowners mitigate the wildfire risk on their property with education and financial assistance. Homeowners who opt-in to the Wildfire Partners program receive a certification that their property has the proper mitigation for wildfires. In exchange, insurance companies recognize this certification as proof of mitigation efforts and agree to provide coverage for certified homes. The program is funded in part by Boulder County, along with state and federal grants.

This voluntary and collaborative effort would be inexpensive compared to the costly top-down approaches of states like California to dealing with home insurance. While California has instituted insurance price controls and mandates that have forced homeowners onto a bare bones state-run plan, Colorado has not needed to resort to such policies.

By leading a collaborative effort with the state’s property insurers, Montana can avoid the pitfalls of states like California and empower the private marketplace to overcome the challenges presented by unnaturally severe wildfires.