In his 2016 book, The End of Average, Todd Rose recounts a story from the 1950’s when the U.S. Air Force faced a major challenge. Pilots were struggling to control their planes leading to serious accidents and fatalities. Initial suspicions were that the jets were too advanced or that pilot training was insufficient, but the real issue lay in the general design of the cockpits.

The Air Force conducted a study of over 4,000 pilots on 10 physical dimensions of cockpit design. The assumption was that, if cockpits fit the average dimensions of a pilot, the majority of pilots would be accommodated. Surprisingly, not a single pilot out of the 4,000 fit within the average dimensions!

This revelation was startling because it challenged the prevailing assumption that a one-size-fits-all design works for most people. The conclusion was clear – designing cockpits based on the “average” pilot was unworkable because such specifications fit no one.

Over the last six months, we have demonstrated that the state of Montana is struggling with a similar problem in education. Through a highly prescriptive set of laws, rules, and agreements, the state education establishment is attempting to treat everyone the same – students, families, teachers, and administrators. Yet under such a “unitary” approach, student achievement outcomes have been sinking for at least 12 years.

In 2023, Montana’s legislature opened the door to a fundamentally different approach. With the passage of a series of bills that support education freedom, there is a historic opportunity to transition from a unitary system to one that embraces pluralism. According to Ashley Rogers Berner, the author of No One Way to School: Pluralism and American Public Education, education pluralism is defined as “changing the structure of public education so that state governments fund and hold accountable a wide variety of schools, including religions ones, but do not necessarily operate them.”

Under this new approach, parents can choose freely from among a variety of different high-quality education options. New schools of choice can be started outside prescriptive district and state regulations. Families can use public funds to purchase the specialized education services that their children need.

Yet even with the laws in place, such a change will not happen on its own. It requires a basic shift in how families, educators, civic leaders, donors, and all community members define and participate in education. Montanans must begin to see education as an integrated part of a healthy and prosperous “civil society.”

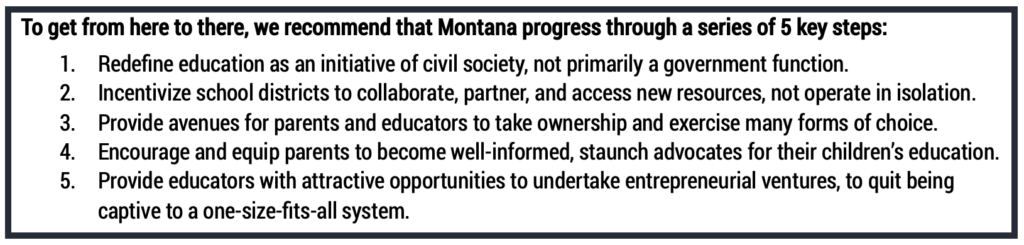

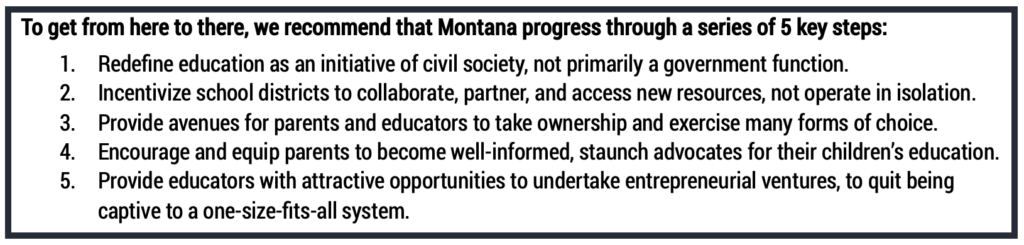

The remainder of this article will describe what it would look like for Montana to complete each of these five steps.

Redefine education as an initiative of civil society, not primarily a government function.

Civil society refers to the social organizations and voluntary associations of citizens acting together to advance common interests, care for each-others’ well-being, provide education and training, practice faith, and strengthen community flourishing. Civil society is an entire sector of community life that spans independent non-profit organizations, philanthropies, charities, academia, churches, social clubs, and personal affiliations.

Until recently, Montana schools have primarily been a function of government, detached from the influence of innovation, competition, business, civic, and faith-based organizations. Top-down regulatory control has undermined the role of parents and made families passive consumers of K-12 education, expected to send their child to a one-size-fits-all, district assigned school.

This assignment system allows for orderly placement into schools but has not yielded sustained benefits because it discourages parents from being active participants in their children’s education. Instead of drawing on the resources and supports of civil society to educate the next generation, school districts frequently act in isolation with regulatory compliance as their agenda. Consider the following two points:

- A June 2023 study conducted by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University revealed that charter school students have been outperforming district school students since 2000. Academic gains were even higher among students enrolled at schools operated by a charter [school] management organization.

- Researchers at the University of Arkansas surveyed over a dozen studies to better understand the connection between school choice, academic, and character development. They found that students in schools of choice saw higher graduation rates and college enrollment. Furthermore, several studies revealed that school choice improved civic engagement, tolerance, and charitable giving.

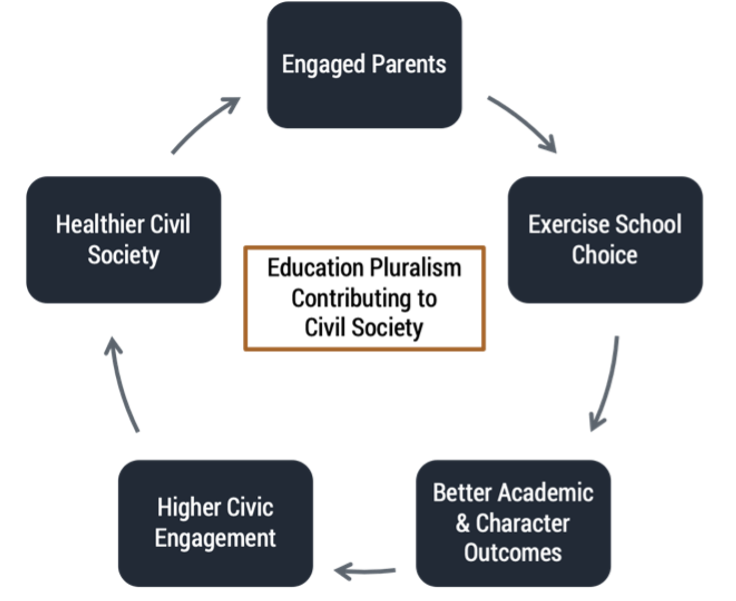

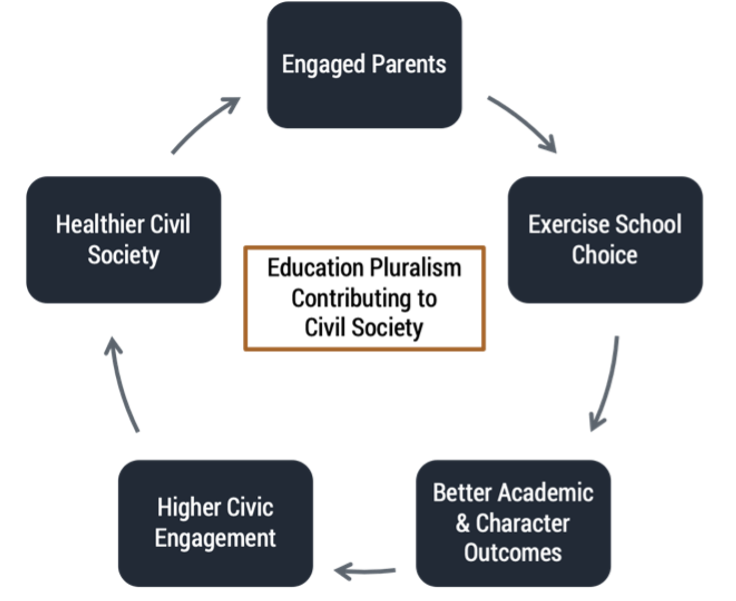

To successfully redefine education as an initiative of civil society begins with redefining two key roles. (1) Entrepreneurial educators must be encouraged to form new public and private schools independently of districts. (2) Parents must begin choosing the best schools for their children from the numerous options available to them, from online and homeschooling to schools of choice and traditional district schools.

In doing so, studies show that students are more likely to experience better academic outcomes and grow to become more engaged community members, eager to direct resources, talent, leadership, and funding to support a sector of education pluralism for the next generation of students.

And so, the cycle continues.

Incentivize school districts to collaborate, partner, and access new resources, not operate in isolation.

As the chart below shows, public schools are responsible for a broad range of services that extend far beyond core academic instruction. However, an overwhelming number of laws and regulations limit how traditional public schools can respond to the ever-changing needs of students.

In the 2021 session alone, the Montana legislature debated 148 bills on K-12 education, regulating everything from funding, spending, school board elections, teacher benefits, facility financing, and school operations. Those bills that passed were added to a 1,374 page document with 126 chapters of statutes that schools must abide by as government agencies.

If Montana public schools are to deliver an education that prepares students to flourish after graduation, such a system of government compliance is unsustainable. Schools must be freed to access new, much needed resources beyond government requirements.

In building partnerships with the many non-government organizations of civil society, school districts do not have to go it alone to deliver high quality programs and services. Most importantly, teachers and school leaders do not have to reinvent the wheel every time they want to do something new or innovative.

Take for example offering a career and technical program. Rather than creating a program from scratch, a partnership with local employers and industry leaders may bring the people, facilities, expertise, and career pathways from outside the district to make development and launch much easier and faster.

When new schools of choice are formed by entrepreneurial educators, there are opportunities to initiate partnerships with non-profit organizations, philanthropies, charities, academic institutions, churches, social clubs, youth programs, and civic organizations. The resources that these partnerships provide can include everything from facilities, equipment, transportation, extracurricular programs, arts and cultural experiences, and expertise in such areas as character, faith, health, nutrition, tutoring, mentoring, and family services.

Provide avenues for parents to take ownership in education and exercise many forms of choice.

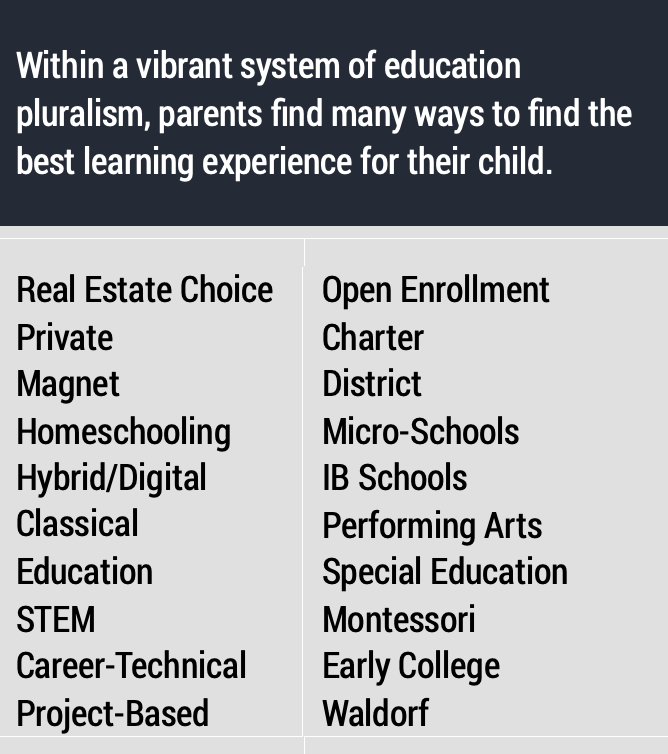

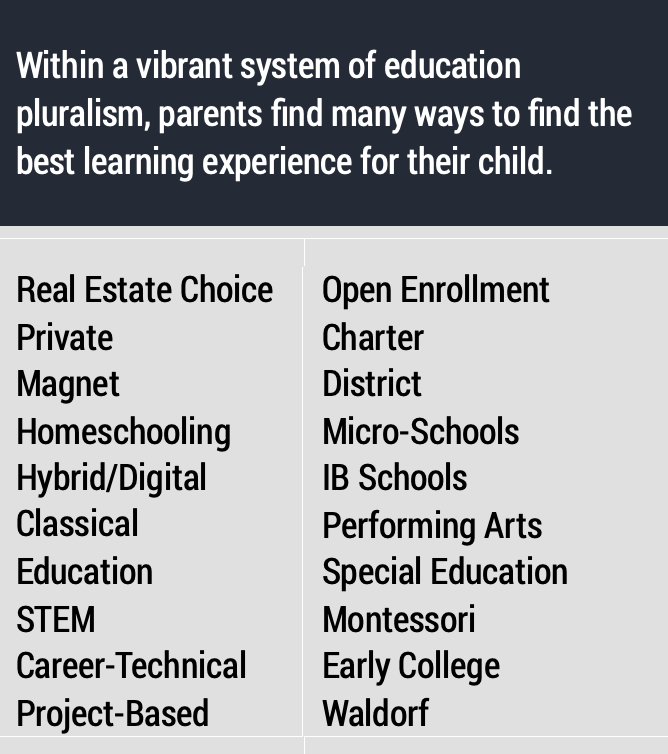

There has always been school choice for Montana families with the money to buy homes in zip codes with successful schools or pay tuition to send their children to a private school. Unfortunately, these opportunities remain limited to a very small and affluent segment of the population.

To fully embrace education pluralism, Montanans must be able to access the schools of their choice regardless of income, location, academic ability, or educational needs. One way to accomplish this is through an open enrollment system. Even between schools within the same district, the quality and availability of academic, athletic, arts, technology, or career programs often differs greatly. Giving families the freedom to choose between districts and between schools within districts, removes a key barrier that can prevent students from accessing the schools of their choosing.

One step further, is to create an environment where entrepreneurial educators are encouraged to find innovative ways to improve instruction and serve students. This, in fact, is the original purpose of charter schools dating back to the 1990s, to act as proving grounds where educators can redefine how children and families get served.

Since the first charter school law was passed, families across the country have benefitted from educational entrepreneurship through the spread of schools that offer distinct curriculum, ways of teaching, program designs, school schedules, behavioral norms, even college and career tracks.

In keeping with Berner’s definition, educational pluralism requires that funding channels become equally available and accessible. In the same way that open enrollment removes residential barriers to quality schools, opening new funding channels to parents and schools removes many of the financial barriers that can limit the exercise of choice.

Instead of a K-12 system where district, charter, and private schools vie for political power, money, and students, parents must have the decision-making authority to choose from a robust menu of options delivered by passionate, mission-driven educators who take responsibility for getting results.

Encourage and equip parents to become well-informed, staunch advocates for their children’s education.

In October 2020, lifelong school choice advocate, Virginia Walden Ford, published a chapter in School Choice Myths: Setting the Record Straight on Education Freedom titled “Only Rich Parents Can Make Good Choices.”

Ford rejects the myth that “poor parents lack the ‘resources’ to choose good schools, the ‘support systems’ to make choices, the ‘time’ to compare and contrast schools, and the ‘social networks’ necessary to understand the differences between good and bad schools…” Through her experiences working with low-income families in Washington, DC, Ford argues that all parents, regardless of their financial standing, possess the desire and ability to choose the best educational pathways for their children.

If upper- and middle-class parents are already making choices for their children, and Ford’s experience demonstrates that low-income families are equally capable, then shouldn’t it be assumed that ALL parents want the best for their children? And where there is a will, parents will find a way.

The sharing of knowledge and experience is one of the most important functions of a civil society, connecting parents with information, resources, and other caregivers to guide their choice-making. In a vibrant civil society, families are not limited to one source of information but can readily turn to community based media, social clubs, youth programs, online resources, seminars, church communities, as well as the schools themselves to make informed decisions about their child’s education.

Again, parents move from passive consumers to active and informed decision-makers as they constantly seek the best resources and expertise for their children.

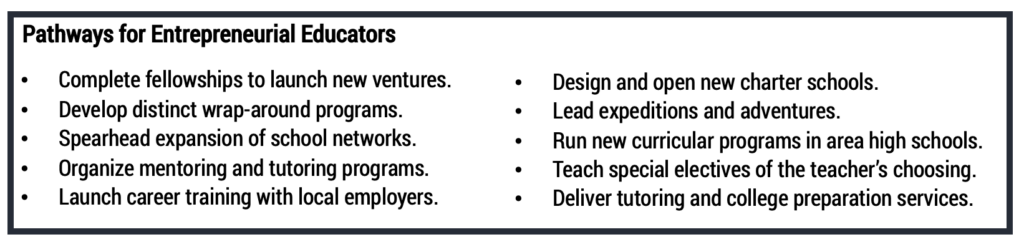

Provide educators with attractive opportunities to undertake entrepreneurial ventures, to quit being captive to a one size fits all system.

The government-district system of schooling grew from the 19th century based on the premise that education should be compulsory, uniform, standardized, and assigned. No matter how many laws are passed to amend the system, many of the underlying controls over schools remain the same.

Within a one-size-fits-all system, creativity, innovation, and the entrepreneurial spirit are stifled, yet these are precisely the motivators that can drive education improvement.

People are not called to K-12 education because they seek a bureaucratic and heavily regulated system where everyone gets treated the same. They are called because they have a passion for working with children, contributing their unique talents, and finding new ways to cultivate excitement for learning. Unfortunately, this passion and energy dries up if not directed towards the benefit of students, professional growth, and upward mobility.

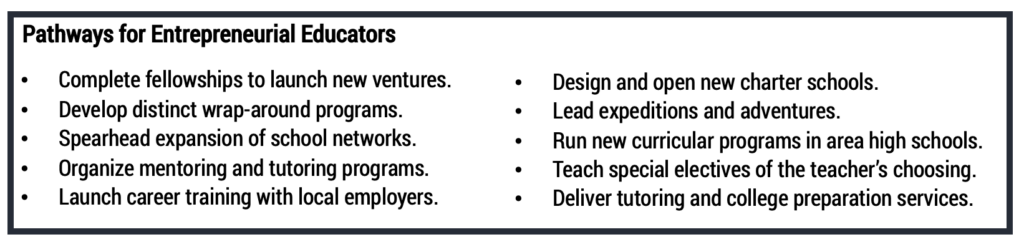

Allowing educators to explore opportunities to innovate, improve, and start their own ventures will only support the broader educational landscape. In a healthy system of education pluralism, educators often find outlets in some of the following ways.

Giving educators such meaningful channels to follow their passions, benefit from their hard work, and earn leadership roles is a pivotal shift towards education pluralism. It continues to break down the one-size-fits-all system by enabling educators to leverage their interests and expertise in ways that truly benefit students and society.

In an environment that values creativity, autonomy, and the entrepreneurial spirit, Montana can cultivate a generation of educators who are not just purveyors of standardized academic instruction, but pioneers of educational excellence for every child and family.

In Conclusion

Montana’s citizens have just begun their journey towards education pluralism. However, it is the start of any endeavor that is often the most fraught with challenges.

In the coming years, there will be many forks in the road, tough decisions to be made, and great debates to be had. As opponents of this transition from government to civil society lobby policy makers in the stage legislature and district board rooms, it will be tempting to fall back into the old ways of relying on an isolated one-size-fits-all system of K-12 education. In doing so, Montana would risk missing an extraordinary opportunity to leverage the entirety of civil society to benefit schools and students.

Montana’s parents, non-profit organizations, philanthropists, faith communities, charities, and civic groups have so much to offer K-12 education in the quest to build a flourishing environment of opportunity for children and educators. This collective transition towards educational pluralism ensures that K-12 education reflects and respects the diverse needs and aspirations of Montana’s students.