The Irony Of A Burn Ban

"Policymakers must ask whether the minuscule risk of an escaped prescribed burn is worth doing nothing, allowing fuels to build up and putting the forest at a higher risk of an all-consuming destructive wildfire."

Last week U.S. Forest Service Chief Randy Moore announced that the agency will stop using prescribed fire as a forest management tool for most of the summer. Moore has instituted a 90-day halt on all prescribed burns on National Forest System lands while the agency reviews its burn protocols and practices in light of the Hermits Peak Fire in New Mexico. The wildfire began as a prescribed fire set by the Forest Service in early April, but after weather conditions changed abruptly, it escaped and grew into the largest fire in the state’s history.

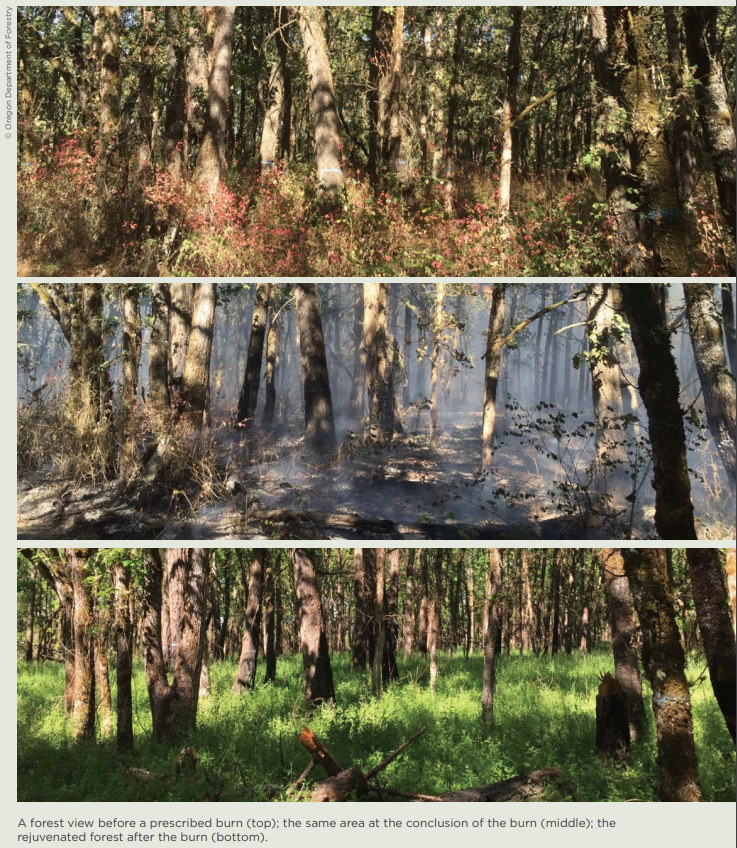

Prescribed burns are an essential tool to reduce the overgrowth and accumulated fuel loads that blanket many national forests and contribute to catastrophic wildfires. Low-intensity fire applied to a forest in the carefully planned and monitored manner of a prescribed burn helps reduce the fuel buildup, reducing fire risk and intensity. Ironically, the scale and intensity of the Hermits Peak Fire emphasizes the need to do more prescribed burns. If fuel treatments, including prescribed burns and mechanical thinning, had been applied to the landscape more regularly, the prescribed burn in New Mexico would have been significantly less likely to become a wildfire after escaping the planned burn area.

As wildfires are growing increasingly catastrophic, the Forest Service needs to use more active management to restore national forests and tackle growing fire risk. Prescribed fire is an important tool, and more than 99.8 percent of Forest Service prescribed burn projects go according to plan. Instead of halting prescribed burns nationwide—a reactionary and blunt response to an unfortunate, if rare, tragedy—the agency should be exploring ways to scale up the use of prescribed burns when and where conditions allow.

The Forest Service has taken an important step in promoting forest restoration by setting a goal to treat an additional 50 million acres of forests with fuel treatments including prescribed burning, thinning and pruning. While thinning and prescribed fire together provide the best opportunity for reducing wildfire risk, forest thinning is restricted by law, regulation or terrain on about half of the national forest lands in the West. Prescribed burns, which are much cheaper on a per acre basis, are therefore the main treatment available on many landscapes. Stopping prescribed burning altogether for the spring and early summer—a window when conditions are usually safer to conduct burns in Montana—could force many agency forest restoration projects to fall behind.

While day-of conditions including wind, air quality, and personnel availability ultimately must align to conduct a prescribed burn, many prescribed burn projects were planned for this spring in the state. Crews in the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, for example, were planning to conduct multiple prescribed burn projects in coming months as part of the Bozeman Municipal Watershed Project. They were just waiting for the right weather window. But now, with the nationwide burn halt, those fuels will remain on the ground, at risk of feeding a catastrophic wildfire and destroying Bozeman’s water source. These local stories join similar anecdotes from around the country, with foresters and experts left frustrated that their projects are all being stopped because of conditions in other parts of the country.

At the end of the day, there is some risk to prescribed fires, but that risk must be compared to the risk of not conducting fuel treatments and having the forest burn completely. Policymakers must ask whether the minuscule risk of an escaped prescribed burn is worth doing nothing, allowing fuels to build up and putting the forest at a higher risk of an all-consuming destructive wildfire.

They should also question why prescribed burns, which produce much less smoke than a wildfire, count against a state’s Clean Air Act compliance, but a wildfire does not. These policies are designed to be risk-averse when it comes to prescribed burns without weighing the risks of doing no active management and having forests become tinder ready to go up in flames and that needs to be changed.

To get serious about reducing wildfire risk, forest managers need tools to be available to them. Prescribed burns are an important part of forest restoration work, yet managers are unable to apply this tool on the ground in safe and managed situations during this halt. The Forest Service should lift the nationwide ban and allow local forest managers to evaluate their unique conditions, risks and rewards to conduct prescribed burns.

Hannah Downey is the policy director at PERC (the Property and Environment Research Center) in Bozeman.