Waiting To Burn

"Even when public land managers, officials and researchers agree that this mitigation work is needed on a landscape, the tools that reduce wildfire severity face a long, bureaucratic process of approvals and delays."

Fire season has begun. Halfway through 2022, wildfires have already burned more than 4.1 million acres in the United States.

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that 80 million acres of national forest land are in need of restoration–for comparison, the state of Montana is just over 94 million acres–yet the agency has treated just two million acres annually in the West in recent decades. With fire seasons getting worse and fire suppression costing taxpayers more than $4.4 billion last year, land managers need to dramatically increase the pace and scale of forest restoration work to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

The Forest Service can reduce wildfire risk by reducing the buildup of fuels in our forests. Two effective methods are mechanical treatments that physically remove downed trees, brush and other dangerous fuels and prescribed burns that reduce fuels through carefully planned, low-intensity fires. Especially when used together, these tools can be highly successful in reducing wildfire severity. During last year’s Bootleg Fire in Oregon, for example, firefighters reported areas previously treated with both methods showed reduced fire intensity and a more manageable ground fire.

(Above: Bootleg Fire, Oregon)

But environmental review requirements and litigation can hold these projects up for years. Even when public land managers, officials and researchers agree that this mitigation work is needed on a landscape, the tools that reduce wildfire severity face a long, bureaucratic process of approvals and delays. Meanwhile, the areas that need treatment build up more fuels and wildfire risk.

New research from my colleagues at PERC explores how the regulatory requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) increase the time it takes to implement fuel treatments through direct and indirect channels. Though NEPA is intended to encourage careful scrutiny of projects that could harm the environment, it can also delay and increase the costs of environmentally beneficial projects—especially forest management projects.

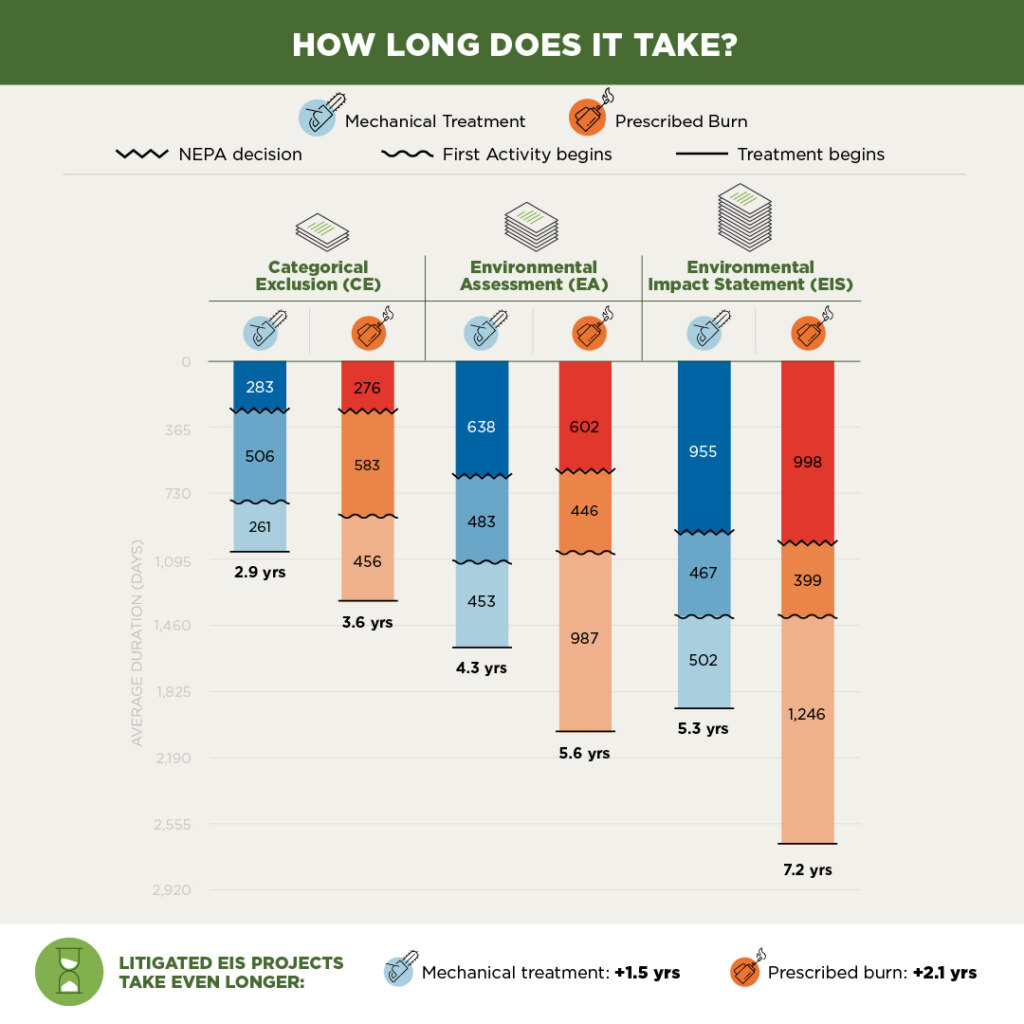

A proposed Forest Service timber harvest or burn has to go through the NEPA process, but there are various levels of stringency for evaluating projects based on how significant the environmental impacts are expected to be:

- Categorical Exclusion: The project is exempted from stringent review.

- Environmental Assessment: Project review is required to rule out significant environmental impacts.

- Environmental Impact Statement: The project is subject to a comprehensive NEPA analysis examining environmental impacts and alternatives.

The more stringent the NEPA review, the longer the process. For example, it takes the average mechanical thinning project under 10 months for approval if it has a categorical exclusion. The average mechanical thinning project that requires an environmental impact statement, on the other hand, takes more than 2 years and 7 months to be approved.

For projects that are ultimately litigated, these timelines stretch even longer. For projects that require an environmental impact statement and are eventually litigated, NEPA review takes an average of 2.1 years longer for a prescribed burn and 1.5 years longer for mechanical treatment. Forest restoration projects are more likely to face litigation than other Forest Service projects, such as trail building or infrastructure development, making them uniquely costly and time-consuming. This is often because managers try to litigation-proof their NEPA reviews in anticipation of legal challenges.

Add in even more time after NEPA approval for factors like additional permitting, funding needs, contracting logistics, weather window delays, and the timeline between project initiation and actually applying a treatment on the ground stretches on for years.

In order for the Forest Service to successfully hit their goal to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration work in the next 10 years, the agency will have to address the challenges that come from the environmental review process and litigation. Cutting regulatory red tape, through approaches that include expanding categorical exclusions, would certainly help. Requiring lawsuits to be filed quickly would also reduce timelines by making litigation less disruptive. The risk of catastrophic wildfires can be reduced, but it will require these types of meaningful changes to enable work to happen on the ground much more quickly.

Read the full report “Does Environmental Review Worsen the Wildfire Crisis?” by Eric Edwards and Sara Sutherland

Hannah Downey is the policy director at PERC (the Property and Environment Research Center) in Bozeman.